m Robot - Moving category Culture of the United Kingdom to

Category:British culture per

CFD at

Wikipedia:Categories for discussion/Log/2011 March 14. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:Milk clouds in tea.jpeg|200px|thumb|right|Black tea with milk]] |

[[Image:Milk clouds in tea.jpeg|200px|thumb|right|Black tea with milk]] |

||

Since the 18th century the [[British people|British]] have been the largest per capita tea consumers in the world, with each person consuming on average 2.5 kg per year.<ref name=waning>[http://www.foodanddrinkeurope.com/Consumer-Trends/Britons-have-less-time-for-tea “Britons have less time for tea],” ''Food & Drink''. 16 June 2003. ''(Retrieved 2010-05-16.)''</ref> The popularity of tea occasioned the furtive export of slips to tea plants from China to [[British India]] and its [[History of tea in India|commercial culture there]], beginning in in 1840; British interests controlled tea production in the subcontinent. Tea, |

Since the 18th century the [[British people|British]] have been the largest per capita tea consumers in the world, with each person consuming on average 2.5 kg per year.<ref name=waning>[http://www.foodanddrinkeurope.com/Consumer-Trends/Britons-have-less-time-for-tea “Britons have less time for tea],” ''Food & Drink''. 16 June 2003. ''(Retrieved 2010-05-16.)''</ref> The popularity of tea occasioned the furtive export of slips to tea plants from China to [[British India]] and its [[History of tea in India|commercial culture there]], beginning in in 1840; British interests controlled tea production in the subcontinent. Tea,bfg |

||

an upper-class drink in Europe, became the infusion of every class in Great Britain in the course of the 18th century and has remained so. |

|||

As tea spread throughout the [[United Kingdom]] in the 19th century, people started to lay out [[tea garden]]s and hold [[tea dance]]s. These would include watching fireworks or a dinner party and dance, concluding with a nice evening tea. The tea gardens lost value after [[World War II]] but tea dances are still held today in the United Kingdom. |

As tea spread throughout the [[United Kingdom]] in the 19th century, people started to lay out [[tea garden]]s and hold [[tea dance]]s. These would include watching fireworks or a dinner party and dance, concluding with a nice evening tea. The tea gardens lost value after [[World War II]] but tea dances are still held today in the United Kingdom. |

||

Revision as of 18:00, 25 March 2011

Since the 18th century the British have been the largest per capita tea consumers in the world, with each person consuming on average 2.5 kg per year. [1] The popularity of tea occasioned the furtive export of slips to tea plants from China to British India and its commercial culture there, beginning in in 1840; British interests controlled tea production in the subcontinent. Tea,bfg

an upper-class drink in Europe, became the infusion of every class in Great Britain in the course of the 18th century and has remained so.

As tea spread throughout the United Kingdom in the 19th century, people started to lay out tea gardens and hold tea dances. These would include watching fireworks or a dinner party and dance, concluding with a nice evening tea. The tea gardens lost value after World War II but tea dances are still held today in the United Kingdom.

In Britain tea is usually black tea served with milk (never cream; the cream of a " cream tea" is clotted cream, served over fruit, not in the tea) and sometimes with sugar. Strong tea served with lots of milk and often two teaspoons of sugar, usually in a mug, is commonly referred to as builder's tea. Much of the time in the United Kingdom, tea drinking is not the delicate, refined cultural expression that the rest of the world imagines—a cup (or commonly a mug) of tea is something drunk often, with some people drinking six or more cups of tea a day. Employers generally allow breaks for tea and sometimes biscuits to be served.

Brief history

Before it became Britain's number one drink, China tea was introduced in the coffeehouses of London shortly before the Stuart Restoration (1660); about that time Thomas Garraway, a coffeehouse owner in London, had to explain the new beverage in pamphlet and an advertisement in Mercurius Politicus for 30 September 1658 offered "That Excellent, and by all Physicians approved, China drink, called by the Chineans, Tcha, by other nations Tay alias Tee, ...sold at the Sultaness-head, ye Cophee-house in Sweetings-Rents, by the Royal Exchange, London". [2] In London "Coffee, chocolate and a kind of drink called tee" were "sold in almost every street in 1659", according to Thomas Rugge's Diurnall. [3] Tea was mainly consumed by the fashionably rich: Samuel Pepys, curious for every novelty, tasted the new drink in 1660: [25 September] "I did send for a cup of tee, (a China drink) of which I had never had drunk before". Two pounds, two ounces were formally presented to Charles II by the British East India Company that same year. [4] Introduced at court in 1662 by Charles II's Portuguese queen, Catherine of Braganza, the act of drinking tea quickly spread throughout court and country and to the English bourgeoisie. The British East India company, which had been supplied with tea at the Dutch factory of Batavia imported it directly from China from 1669. [5] Between 1720 and 1750 the imports of tea to Britain through the British East India Company more than quadrupled. [6] Fernand Braudel queried, "is it true to say the new drink replaced gin in England?" [7]By 1766 exports from Canton stood at 6 million pounds on British boats, compared with 4.5 on Dutch ships, 2.4 on Swedish, 2.1 on French. [8] Veritable "tea fleets" grew up Tea was particularly interesting to the Atlantic world not only because it was easy to cultivate but also because of how easy it was to prepare and its ability to revive the spirits and cure mild colds: [9] "Home, and there find my wife making of tea," Pepys recorded under 28 June 1667, "a drink which Mr. Pelling the Pottecary tells her is good for her colds and defluxions."

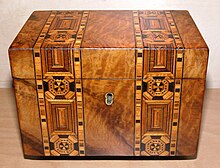

The earliest English equipages for making tea date to the 1660s. Small porcelain tea bowls were used by the fashionable; they were occasionally shipped with the tea itself. Tea-drinking spurred the search for a European imitation of Chinese porcelain, first successfully produced in England at the Chelsea porcelain manufactory, established around 1743-45 and quickly imitated.

Between 1872 and 1884 the supply of tea to the empire had increased with the expansion of the British Empire’s railroad to the east. The demand however was not proportional, which caused the prices to rise. Nevertheless, from 1884 onward due to new innovation in tea preparation the price of tea dropped and remained relatively low throughout the first half of the 20th century. Soon afterwards London became the center of international tea trade. [10] With high tea imports also came a large increase in the demand for porcelain . The demand for tea cup, pots and dishes increased to go along with this popular new drink. [11] Now, people in Britain drink tea multiple times a day. As the years passed it became a drink less associated with high society as people of all classes drink tea today which can be enjoyed in many different flavours and ways.

British tea ritual

Even very slightly formal events can be a cause for cups and saucers to be used instead of mugs. A typical semi-formal British tea ritual might run as follows (the host performing all actions unless noted):

- The kettle is briefly boiled and water poured into a tea pot.

- Water is swirled around the pot to warm it and then poured out.

- Loose tea leaves—nowadays often tea bags or the dust from a ripped-open tea bag—are then added to the pot.

- Water is added to the pot and allowed to brew for several minutes while a tea cosy is placed on the pot to keep the tea warm. If the tea is allowed to brew for too long, id est more than 10 minutes, it will become "stewed", resulting in a very bitter, astringent taste.

- Milk may be added to the tea cup, the host asking the guest if milk is wanted, although milk may alternatively be added after the tea is poured.

- A tea strainer, like a miniature sieve, is placed over the top of the cup and the tea poured in.

- The straight black tea is then given to guests and they are allowed to add milk and sugar to their taste.

- The pot will normally hold enough tea so as not to be empty after filling the cups of all the guests. If this is the case, the tea cosy is replaced after everyone has been served.

Whether to put milk into the cup before or after the tea is, and has been since at least the late 20th century, a matter of some debate with claims that adding milk at the different times alters the flavour of the tea. "MIF", "milk-in-first" retains some connotations of the assembly-line service of a transport caf, and is considered naff or non-U.

There is also a proper manner in which to drink tea when using a cup and saucer.[ citation needed] If one is seated at a table, the proper manner to drink tea is to raise the teacup only, placing it back into the saucer in between sips. When standing or sitting in a chair without a table, one holds the tea saucer with the off hand and the tea cup in the dominant hand. When not in use, the tea cup is placed back in the tea saucer and held in one's lap or at waist height. In either event, the tea cup should never be held or waved in the air.

Drinking tea from the saucer (poured from the cup in order to cool it) was not uncommon at one time but is now almost universally considered a breach of etiquette. Sir Winston Churchill was a famous advocate of this practice, much to the chagrin of many members of the British gentry with whom he had to consort in government roles.

Tea as a meal

Tea is not only the name of the beverage, but of a late afternoon light meal at four o'clock, irrespective of the beverage consumed. Anna Russell, Duchess of Bedford is credited with the creation of the meal circa 1800. She thought of the idea to ward off hunger between luncheon and dinner, which was served later and later. The tradition continues to this day.

There used to be a tradition of tea rooms in the UK which provided the traditional fare of cream and jam on scones, a combination commonly known as cream tea. However, these establishments have declined in popularity since World War II. In Devon and Cornwall particularly, cream teas are a speciality. A.B.C. tea shops and Lyons Corner Houses were a successful chain of such establishments. It is a common misconception that cream tea refers to tea served with cream (as opposed to milk). This is certainly not the case,although sometimes a slice of banana is added, a tradition emanating from the Caribbean. It simply means that tea is served with a scone with clotted cream and jam.

Industrial Revolution

Some scholars suggest that tea played a role in British Industrial Revolution. Afternoon tea possibly became a way to increase the number of hours labourers could work in factories; the stimulants in the tea, accompanied by sugary snacks, such as cheese based puffs and the humble currant bun, would give workers energy to finish out the day's work. Further, tea helped alleviate some of the consequences of the urbanization that accompanied the industrial revolution: drinking tea required boiling one's water, thereby killing water-borne diseases like dysentery, cholera, and typhoid. [12]

Tea cards

In the United Kingdom, and to a certain extent, Canada, a number of varieties of loose tea sold in packets from the 1940s to the 1980s contained tea cards. These were illustrated cards roughly the same size as cigarette cards and intended to be collected by children. Perhaps the best known were Typhoo tea and Brooke Bond (manufacturer of PG Tips), the latter of whom also provided albums for collectors to keep their cards in. Some renowned artists were commissioned to illustrate the cards including Charles Tunnicliffe. Many of these card collections are now valuable collectors' items.

Tea today

In 2003, Datamonitor reported that regular tea drinking in the United Kingdom was on the decline. [1] There was a 10¼ percent decline in the purchase of normal teabags in Britain between 1997 and 2002. [1] Counter-intuitively, it was not coffee that was filling the gap since the sales of ground coffee also fell during the same period. [1] Britons were instead filling the warm drinks void with health-oriented beverages like fruit and/or herbal teas, consumption of which increased 50 percent from 1997 to 2002. [1] A further, unexpected, statistic is that the sales of decaffeinated tea and coffee fell even faster during this period than the sale of the regular varieties. [1]

Further reading

- Julie E. Fromer. A Necessary Luxury: Tea in Victorian England (Ohio University Press, 2008), 375pp

References

- ^ a b c d e f “Britons have less time for tea,” Food & Drink. 16 June 2003. (Retrieved 2010-05-16.)

- ^ Niall Ferguson, Empire: the rise and demise of the British world order, (2004:11).

- ^ Rugge's Diurnall is preserved in the British Library (Add. MSS. 10,116-117); it was published as The diurnal of Thomas Rugg, 1659-1661, William Lewis Sachse ed., (1961).

- ^ Richard, Lord Braybrooke, ed., note in The Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys, F.R.S., vol. I :109.

- ^ Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism: The Structures of Everyday Life (1979) 1981:251; Guerty, P. M., and Kevin Switaj. 2004. "Tea, porcelain, and sugar in the British Atlantic world." OAH Magazine of History 18.3 (2004: 56-59).

- ^ Sir George Staunton's figure, starting in 1693, is quoted, e.g., in Walvin, James. 1997. "A taste of empire, 1600-1800". (cover story). History Today 47.1 (2001: 11).

- ^ Braudel 1981:252.

- ^ Braudel 1981:251.

- ^ Guerty and Switaj 2004.

- ^ Nguyen, D. T., and M. Rose. 1987. Demand for tea in the UK 1874-1938: An econometric study. Journal of Development Studies 24.1 (2010): 43.

- ^ Guerty, P. M., and Kevin Switaj. 2004. Tea, porcelain, and sugar in the british atlantic world. OAH Magazine of History 18 (3) (04): 56-9.

- ^ Tea and the Industrial Revolution