Hologenomics is the omics study of hologenomes. A hologenome is the whole set of genomes of a holobiont, an organism together with all co-habitating microbes, other life forms, and viruses. [1] While the term hologenome originated from the hologenome theory of evolution, which postulates that natural selection occurs on the holobiont level, [2] hologenomics uses an integrative framework to investigate interactions between the host and its associated species. Examples include gut microbe [3] or viral [4] genomes linked to human or animal genomes for host-microbe interaction research. [5] Hologenomics approaches have also been used to explain genetic diversity in the microbial communities of marine sponges. [6]

History

The origins of hologenomics revolves around the hologenome theory of evolution, which describes individual multicellular organisms, microbes, and viruses establishing symbiotic relationships and undergoing coevolution together. [2] [7] Richard Jefferson introduced the term 'hologenome' to describe the host-symbiont genome as an evolutionary unit. [8] Prior to this, Lynn Margulis used the term 'holobiont' to describe hosts and their associated species as an ecological unit. [9]

Eukaryotes-prokaryotes coevolution

Earliest evidence of multicellular-unicellular interactions are seen in sponges, which are a well studied hologenomic system. Porifera are often described as holobionts because they harbor a wide range of bacteria, archaea and algae. Microbial communities present have been observed in facilitating metabolic functions and immune responses. [10] Offspring inherit these microbial colonies via vertical and/or horizontal transmission. [10] Symbiont colonies are transferred through parental gametes in vertical transmission, whereas offspring acquire same colonies from their environment in horizontal transmission. Vertical transmission is also seen in terrestrial organisms like C. ocellatus, where gammaproteobacteria in the parental gut is vertically transferred through egg contamination. [11]

Criticism

The hologenome theory evolution is not fully accepted, and research in microbial-host phylogenetics is ongoing. Rather than the selection of corals with certain symbiotic microbial communities, coral bleaching may simply be a result of environmental stressors, and bacterial presence in bleached coral may be explained simply as opportunistic colonization. [12] Ubiquity testing also revealed many different bacterial and algal symbionts that are not associated with a single species of coral, [13] suggesting that hologenomics just identifies and validates mechanistic interactions between pathogens, microbes, and their hosts. [14]

Examples of discoveries with hologenomic approaches

- Nanopore sequencing - Profiling organelle genomes in the holobiont C. ashmeadii revealed that Rhodospirillaceae was dominant among six putative endosymbionts. [15]

- 16S rRNA sequencing - Sponge-specific microbial communities were profiled with rRNA and rRNA gene sequencing, providing insight into bacterial diversity and activity of those communities. [16]

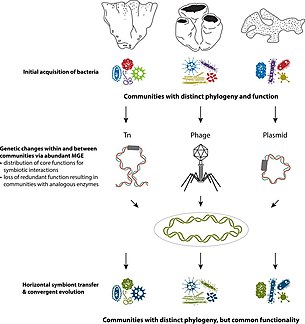

- Metagenomic DNA - Gene profiles of sponge microbiomes were compared to surrounding planktonic communities. [17] Core function genes of microbial symbionts expressed consistent patterns of phylogeny and function that differ from planktonic samples, demonstrating host-symbiont co-evolution. [17]

Applications

Medicine

It's hypothesized the continued incidence non-infectious diseases is a result of modernization reducing the diversity of symbiotic microbes. [14] The human microbiome has also been correlated to numerous etiologies of non-communicable disease, such as brain disorders, [18] cancer, [19] [20] and heart disease. [21] Interactions between human microbiome and human health are complex and suggest a hologenomic approach.

Disease biomarkers can be found by investigating lifestyle, genomic differences, and mRNA/ protein/ metabolite profiles of the patient and their microbiota. [14] For investigating microbiomes and specifically microbiota subcommunities that may contribute to a disease phenotype, longitudinal studies are recommended as everyone has a personalized microbiome with small differences in microbiome phylotypes. [14] A personalized plan managing a person’s microbiome can then be developed, with prebiotics nurturing beneficial endogenous microbes, and probiotics manipulating a person’s hologenome. [22]

Immunology

Conditional mutualism, where parasites have mutualistic effects under certain environmental/ecological conditions, have been found with holobiont-holobiont interactions. [23] Maturation of mammalian host immune systems has been known to involve gastrointestinal flora. [24] Understanding microorganism recognition of foreign pathogenic invasion and how host immunity favors the most ideal symbiont may aid in discovering novel therapeutic treatments to combat evolving diseases.

See also

References

- ^ Rosenberg, Eugene; Zilber-Rosenberg, Ilana (2018-04-25). "The hologenome concept of evolution after 10 years". Microbiome. 6 (1): 78. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0457-9. ISSN 2049-2618. PMC 5922317. PMID 29695294.

- ^ a b Number 6 in a series of 7 VHS recordings, A Decade of PCR: Celebrating 10 Years of Amplification, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1994. ISBN 0-87969-473-4.

- ^ Denman, Stuart E.; McSweeney, Christopher S. (2015-02-16). "The Early Impact of Genomics and Metagenomics on Ruminal Microbiology". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 3 (1): 447–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110705. ISSN 2165-8102. PMID 25387109.

- ^ Patowary, Ashok; Chauhan, Rajendra Kumar; Singh, Meghna; KV, Shamsudheen; Periwal, Vinita; KP, Kushwaha; Sapkal, Gajanand N.; Bondre, Vijay P.; Gore, Milind M. (2012-01-01). "De novo identification of viral pathogens from cell culture hologenomes". BMC Research Notes. 5: 11. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-11. ISSN 1756-0500. PMC 3284880. PMID 22226071.

- ^ Miller, William B. Jr. (2013). The Microcosm Within: Evolution and Extinction in the Hologenome. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 978-1612332772.

- ^ Webster, Nicole S.; Thomas, Torsten (2016-05-04). "The Sponge Hologenome". mBio. 7 (2): e00135–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00135-16. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 4850255. PMID 27103626.

- ^ Rosenberg, Eugene; Zilber-Rosenberg, Ilana (2018-04-25). "The hologenomce concept of evolution after 10 years". Microbiome. 6 (1): 78. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0457-9. ISSN 2049-2618. PMC 5922317. PMID 29695294.

- ^ Number 6 in a series of 7 VHS recordings, A Decade of PCR: Celebrating 10 Years of Amplification, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1994. ISBN 0-87969-473-4.

- ^ Margulis, University of Massachusetts Amherst Massachusetts Lynn; Margulis, Lynn; Fester, René (1991). Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation: Speciation and Morphogenesis. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13269-5.

- ^ a b c Webster, Nicole S.; Thomas, Torsten (2016-05-04). "The Sponge Hologenome". mBio. 7 (2): e00135-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00135-16. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 4850255. PMID 27103626.

- ^ Kaiwa, Nahomi; Hosokawa, Takahiro; Kikuchi, Yoshitomo; Nikoh, Naruo; Meng, Xian Ying; Kimura, Nobutada; Ito, Motomi; Fukatsu, Takema (2010-06-01). "Primary Gut Symbiont and Secondary, Sodalis-Allied Symbiont of the Scutellerid Stinkbug Cantao ocellatus". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 76 (11): 3486–3494. Bibcode: 2010ApEnM..76.3486K. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00421-10. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 2876435. PMID 20400564.

- ^ Ainsworth, T. D.; Fine, M.; Roff, G.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O. (2008). "Bacteria are not the primary cause of bleaching in the Mediterranean coral Oculina patagonica". The ISME Journal. 2 (1): 67–73. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.88. ISSN 1751-7362. PMID 18059488. S2CID 1032896.

- ^ Hester, Eric R.; Barott, Katie L.; Nulton, Jim; Vermeij, Mark JA; Rohwer, Forest L. (May 2016). "Stable and sporadic symbiotic communities of coral and algal holobionts". The ISME Journal. 10 (5): 1157–1169. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.190. ISSN 1751-7370. PMC 5029208. PMID 26555246.

- ^ a b c d Theis, Kevin R. (2018-04-10). "Hologenomics: Systems-Level Host Biology". mSystems. 3 (2). doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00164-17. ISSN 2379-5077. PMC 5895875. PMID 29657963.

- ^ Sauvage, Thomas; Schmidt, William E.; Yoon, Hwan Su; Paul, Valerie J.; Fredericq, Suzanne (2019-11-13). "Promising prospects of nanopore sequencing for algal hologenomics and structural variation discovery". BMC Genomics. 20 (1): 850. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6248-2. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 6854639. PMID 31722669.

- ^ Kamke, Janine; Taylor, Michael W.; Schmitt, Susanne (2017-01-07). "Activity profiles for marine sponge-associated bacteria obtained by 16S rRNA vs 16S rRNA gene comparisons". The ISME Journal. 4 (4): 498–508. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.143. ISSN 1751-7370. PMID 20054355.

- ^ a b Fan, Lu; Reynolds, David; Liu, Michael; Stark, Manuel; Kjelleberg, Staffan; Webster, Nicole S.; Thomas, Torsten (2012-07-03). "Functional equivalence and evolutionary convergence in complex communities of microbial sponge symbionts". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (27): E1878–E1887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203287109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3390844. PMID 22699508.

- ^ Zhu, Sibo; Jiang, Yanfeng; Xu, Kelin; Cui, Mei; Ye, Weimin; Zhao, Genming; Jin, Li; Chen, Xingdong (2020-01-17). "The progress of gut microbiome research related to brain disorders". Journal of Neuroinflammation. 17 (1): 25. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-1705-z. ISSN 1742-2094. PMC 6969442. PMID 31952509.

- ^ Xavier, Joao B.; Young, Vincent B.; Skufca, Joseph; Ginty, Fiona; Testerman, Traci; Pearson, Alexander T.; Macklin, Paul; Mitchell, Amir; Shmulevich, Ilya; Xie, Lei; Caporaso, J. Gregory (2020-03-01). "The Cancer Microbiome: Distinguishing Direct and Indirect Effects Requires a Systemic View". Trends in Cancer. 6 (3): 192–204. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.01.004. ISSN 2405-8033. PMC 7098063. PMID 32101723.

- ^ Helmink, Beth A.; Khan, M. A. Wadud; Hermann, Amanda; Gopalakrishnan, Vancheswaran; Wargo, Jennifer A. (2019-03-06). "The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy". Nature Medicine. 25 (3): 377–388. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0377-7. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 30842679. S2CID 71145949.

- ^ Trøseid, Marius; Andersen, Geir Øystein; Broch, Kaspar; Hov, Johannes Roksund (2020-02-01). "The gut microbiome in coronary artery disease and heart failure: Current knowledge and future directions". eBioMedicine. 52: 102649. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102649. ISSN 2352-3964. PMC 7016372. PMID 32062353.

- ^ Young, Vincent B. (2017-03-15). "The role of the microbiome in human health and disease: an introduction for clinicians". BMJ. 356: j831. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j831. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 28298355. S2CID 2443057.

- ^ Dheilly, Nolwenn Marie (2014-07-03). "Holobiont–Holobiont Interactions: Redefining Host–Parasite Interactions". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (7): e1004093. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004093. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 4081813. PMID 24992663.

- ^ Belkaid, Yasmine; Hand, Timothy W. (2014-03-27). "Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammation". Cell. 157 (1): 121–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 4056765. PMID 24679531.