Gliding motility is a type of translocation used by microorganisms that is independent of propulsive structures such as flagella, pili, and fimbriae. [1] Gliding allows microorganisms to travel along the surface of low aqueous films. The mechanisms of this motility are only partially known.

Twitching motility also allows microorganisms to travel along a surface, but this type of movement is jerky and uses pili as its means of transport. Bacterial gliding is a type of gliding motility that can also use pili for propulsion.

The speed of gliding varies between organisms, and the reversal of direction is seemingly regulated by some sort of internal clock. [2] For example the apicomplexans are able to travel at fast rates between 1–10 μm/s. In contrast Myxococcus xanthus bacteria glide at a rate of 0.08 μm/s. [3] [4]

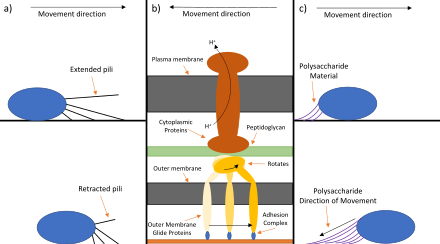

a) type IV pili, b) Specific motility membrane proteins, c) Polysaccharide jet

Cell-invasion and gliding motility have TRAP ( thrombospondin-related anonymous protein), a surface protein, as a common molecular basis that is both essential for infection and locomotion of the invasive apicomplexan parasite. [5] Micronemes are secretory organelles on the apical surface of the apicomplexans used for gliding motility.

In the diagram above, right:

| a) | type IV pili |

| A cell attaches its pili to a surface or object in the direction it is traveling. The proteins in the pili are then broken down to shrink the pili pulling the cell closer to the surface or object that was it was attached to. [6] | |

| b) | Specific motility membrane proteins |

| Transmembrane proteins are attached to the host surface. This adhesion complex can either be specific to a certain type of surface like a certain cell type or generic for any solid surface. Motor proteins attached to an inner membrane force the movement of the internal cell structures in relation to the transmembrane proteins creating net movement. [7] This is driven by the proton motive force. [8] The proteins involved differ between species. An example of a bacterium that uses this mechanism would be Flavobacterium. This mechanism is still being studied and is not well understood. [9] | |

| c) | Polysaccharide jet |

| The cell releases a 'jet' of polysaccharide material behind it propelling it forward. This polysaccharide material is left behind. [10] |

Types of motility

| Part of a series on |

| Microbial and microbot movement |

|---|

|

| Microswimmers |

| Molecular motors |

Bacterial gliding is a process of motility whereby a bacterium can move under its own power. Generally, the process occurs whereby the bacterium moves along a surface in the general direction of its long axis. [11] Gliding may occur via distinctly different mechanisms, depending on the type of bacterium. This type of movement has been observed in phylogenetically diverse bacteria [12] such as cyanobacteria, myxobacteria, cytophaga, flavobacteria, and mycoplasma.

Bacteria move in response to varying climates, water content, presence of other organisms, and firmness of surfaces or media. Gliding has been observed in a wide variety of phyla, and though the mechanisms may vary between bacteria, it is currently understood that it takes place in environments with common characteristics, such as firmness and low-water, which enables the bacterium to still have motility in its surroundings. Such environments with low-water content include biofilms, soil or soil crumbs in tilth, and microbial mats. [11]

Purpose

Gliding, as a form of motility, appears to allow for interactions between bacteria, pathogenesis, and increased social behaviours. It may play an important role in biofilm formation, bacterial virulence, and chemosensing. [13]

Swarming motility

Swarming motility occurs on softer semi-solid and solid surfaces (which usually involves movement of a bacterial population in a coordinated fashion via quorum sensing, using flagella to propel them), or twitching motility [12] on solid surfaces (which involves extension and retraction of type IV pili to drag the bacterium forward). [14]

Proposed mechanisms

The mechanism of gliding might differ between species. Examples of such mechanisms include:

- Motor proteins found within the inner membrane of the bacteria utilize a proton-conducting channel to transduce a mechanical force to the cell surface. [1] The movement of the cytoskeletal microfilaments causes a mechanical force which travels to the adhesion complexes on the substrate to move the cell forward. [15] Motor and regulatory proteins that convert intracellular motion into mechanical forces like traction force have been discovered to be a conserved class of intracellular motors in bacteria that have been adapted to produce cell motility. [15]

- A-motility ( adventurous motility) [11] [13] [16] as a proposed type of gliding motility, involving transient adhesion complexes fixed to the substrate while the organism moves forward. [13] For example, in Myxococcus xanthus, [11] [12] [13] [17] a social bacterium.

- Ejection or secretion of a polysaccharide slime from nozzles at either end of the cell body. [18]

- Energized nano-machinery or large macromolecular assemblies located on the bacterium's cell body. [15]

- " Focal adhesion complexes" and "treadmilling" of surface adhesins distributed along the cell body. [13] [2]

- The gliding motility of Flavobacterium johnsoniae uses a helical track superficially similar to M. xanthus, but via a different mechanism. Here the adhesin SprB is propelled along the cell surface (spiraling from pole to pole), pulling the bacterium along 25 times faster than M. xanthus. [19] Flavobacterium johnsoniae move via a screw-like mechanism and are powered by a proton motive force. [20]

See also

References

- ^ a b Nan, Beiyan (February 2017). "Bacterial gliding motility: Rolling out a consensus model". Current Biology. 27 (4): R154–R156. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.035. PMID 28222296.

- ^ a b Nan, Beiyan; McBride, Mark J.; Chen, Jing; Zusman, David R.; Oster, George (February 2014). "Bacteria that glide with helical tracks". Current Biology. 24 (4): 169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.034. PMC 3964879. PMID 24556443.

- ^ Sibley, L. David; Håkansson, Sebastian; Carruthers, Vern B. (1998-01-01). "Gliding motility: An efficient mechanism for cell penetration". Current Biology. 8 (1): R12–R14. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70008-9. PMID 9427622.

- ^ Sibley, L.D.I. (October 2010). "How apicomplexan parasites move in and out of cells". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 21 (5): 592–8. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.05.009. PMC 2947570. PMID 20580218.

- ^ Sultan, Ali A.; Thathy, Vandana; Frevert, Ute; Robson, Kathryn J.H.; Crisanti, Andrea; Nussenzweig, Victor; Nussenzweig, Ruth S.; Ménard, Robert (1997). "TRAP is necessary for gliding motility and infectivity of plasmodium sporozoites". Cell. 90 (3): 511–522. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80511-5. PMID 9267031.

- ^ Strom, M.S.; Lory, S. (1993-10-01). "Structure-function and Biogenesis of the Type IV Pili". Annual Review of Microbiology. 47 (1): 565–596. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003025. ISSN 0066-4227. PMID 7903032.

- ^ McBride, Mark J. (2001-10-01). "Bacterial gliding motility: Multiple mechanisms for cell movement over surfaces". Annual Review of Microbiology. 55 (1): 49–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.49. ISSN 0066-4227. PMID 11544349.

- ^ Dzink-Fox, J.L.; Leadbetter, E.R.; Godchaux, W. (December 1997). "Acetate acts as a protonophore and differentially affects bead movement and cell migration of the gliding bacterium Cytophaga johnsonae (Flavobacterium johnsoniae)". Microbiology. 143 (12): 3693–3701. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3693. ISSN 1350-0872. PMID 9421895.

- ^ Braun, Timothy F.; Khubbar, Manjeet K.; Saffarini, Daad A.; McBride, Mark J. (September 2005). "Flavobacterium johnsoniae Gliding Motility Genes Identified by mariner Mutagenesis". Journal of Bacteriology. 187 (20): 6943–6952. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.6943-6952.2005. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 1251627. PMID 16199564.

- ^ Hoiczyk, E.; Baumeister, W. (1998-10-22). "The junctional pore complex, a prokaryotic secretion organelle, is the molecular motor underlying gliding motility in cyanobacteria". Current Biology. 8 (21): 1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00487-3. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 9799733.

- ^ a b c d Spormann, Alfred M. (September 1999). "Gliding motility in bacteria: Insights from studies of Myxococcus xanthus". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 63 (3): 621–641. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.621-641.1999. ISSN 1092-2172. PMC 103748. PMID 10477310.

- ^ a b c McBride, M. (2001). "Bacterial gliding motility: Multiple mechanisms for cell movement over surfaces". Annual Review of Microbiology. 55: 49–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.49. PMID 11544349.

- ^ a b c d e Mignot, T.; Shaevitz, J.; Hartzell, P.; Zusman, D. (2007). "Evidence that focal adhesion complexes power bacterial gliding motility". Science. 315 (5813): 853–856. Bibcode: 2007Sci...315..853M. doi: 10.1126/science.1137223. PMC 4095873. PMID 17289998.

- ^ Nan, Beiyan; Zusman, David R. (July 2016). "Novel mechanisms power bacterial gliding motility". Molecular Microbiology. 101 (2): 186–193. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13389. ISSN 1365-2958. PMC 5008027. PMID 27028358.

- ^ a b c Sun, Mingzhai; Wartel, Morgane; Cascales, Eric; Shaevitz, Joshua W.; Mignot, Tâm (2011-05-03). "Motor-driven intracellular transport powers bacterial gliding motility". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (18): 7559–7564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101101108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3088616. PMID 21482768.

- ^ Sliusarenko, O.; Zusman, D.R.; Oster, G. (17 August 2007). "The motors powering A-motility in Myxococcus xanthus are distributed along the cell body". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (21): 7920–7921. doi: 10.1128/JB.00923-07. PMC 2168729. PMID 17704221.

- ^ Luciano, Jennifer; Agrebi, Rym; Le Gall, Anne Valérie; Wartel, Morgane; Fiegna, Francesca; Ducret, Adrien; Brochier-Armanet, Céline; Mignot, Tâm (2011-09-08). "Emergence and modular evolution of a novel motility machinery in bacteria". PLOS Genetics. 7 (9): e1002268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002268. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 3169522. PMID 21931562.

- ^ Merali, Zeeya (3 April 2006). "Bacteria use slime jets to get around". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 1 July 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ Nan, Beiyan (2015). "Bacteria that glide with helical tracks". Curr Biol. 24 (4): R169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.034. PMC 3964879. PMID 24556443.

- ^ Shrivastava, Abhishek (2016). "The Screw-Like Movement of a Gliding Bacterium Is Powered by Spiral Motion of Cell-Surface Adhesins". Biophys. J. 111 (5): 1008–1013. Bibcode: 2016BpJ...111.1008S. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.07.043. PMC 5018149. PMID 27602728.